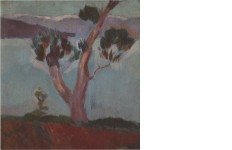

TITΛΟΣ ΕΡΓΟΥΤΟΠΙΟ

ΔΙΑΣΤΑΣΕΙΣ ΕΡΓΟΥΎψος : 46

Πλάτος : 42.5

ΥΛΙΚΟ ΚΑΤΑΣΚΕΥΗΣΕλαιογραφία (Λάδι σε καμβά)

ΥΠΟΓΡΑΦΗ ΚΑΛΛΙΤΕΧΝΗΚάτω Αριστερά

ΧΡΟΝΟΛΟΓΗΣΗ

ΕΛΕΓΧΟΣ ΓΝΗΣΙΟΤΗΤΑΣΔεν έχει ελεγχθεί

Provenance:

Private collection, Athens.

Exhibited:

Thessaloniki, 19th Demetria, organized by the Vafopoulio Cultural Center and the National Gallery and Alexander Soutzos Museum, October-November 1984, no 30 (illustrated in the exhibition catalogue no 16).

Athens, Federation of Greek Industries, Parthenis, June 2004 (illustrated in the exhibition catalogue p.21).

Literature:

Kathimerini newspaper, 13 June 2004.

Light equals colour.

Its that which gives birth to shape.

C. Parthenis

One of Parthenis most brilliantly coloured landscapes, this picture shows the vibrancy of the artists original brushwork and the tense, mobile application of paint that characterises much of his best work. Throughout the painting Parthenis has used his distinctive parallel strokes; in some places, like in the distant mountains, with great diligence and finesse and in others, as in the leafage, with admirable confidence and freedom. Our eye follows the darting movements of his brush, as successive touches of bold colour are seized upon and added to the picture surface. The proliferation and intensity of his colours builds to a climactic pitch as cool acid greens are laid against the hottest of red-browns, and sapphire blues against purples and lilacs. Every feature of the scene appears to be animated by colour.

In 1909, when Parthenis moved to Paris, he found himself in the midst of heated debates concerning colour issues. Upon his return to Greece in 1911 and following his stay in Corfu until 1917 (where he painted some of the most beautiful landscapes of his career), his expressive language matures, drawing from multiple possibilities including the colour expressionism of the fauves combined with Cezannes use of paint as volume, as a structural element.1

The Greek landscape provided Parthenis with the same great challenge that the Chantilly forest or Mont Saint-Victoire had provided Cezanne a few decades earlier, namely how to express through patterns of paint on a flat surface a clearly defined and resonant structure that presented itself to the eye as a series of shapes and volumes (compare Path in Chantilly, 1888 and Mont Saint-Victoire, 1888-90, National Gallery, London.) Both artists tackled this problem head-on, representing their subjects in their own terms and using the orientation of their brushstrokes, the limpidity of their colours and the contrasts of their tones to summarise their visual experience. Colour was the basis of their visual perception and the means by which they expressed form, light and depth, in a way that the picture plane eventually became a field of coloured patches, each patch judged in relation to its neighbours and to the picture as a whole. Tonal gradations and shifts of hue were recorded in adjacent strokes, while their flickering, vibrant intensity captured the power and variable pulse of the landscape.2

Less interested in a descriptive treatment of his subject than in giving prominence to the pictures structural elements and achieving an internal rhythm, Parthenis sets up a solid compositional framework of two prominent horizontal bands to define the foreground and background of this panoramic landscape, and then singles out a tree in the foreground, using it as an organizing motif that also forms a vertical link between land and sky. The curvilinear motifs of the tree branches further enliven the scene, charging the entire composition with a poetic charm.3 In his treatise on the representation of the tree in Greek art, Professor C. Christou notes that the tree holds a prominent position in Parthenis work and his paintings of the specific subject are exceptional4, while, as early as 1920, Z. Papantoniou made the following remark: Parthenis landscapes from Attica, Corfu and Poros take us to the world of ideas. His eye sees into the ideal, as ours does into the natural. The humblest of trees reveals a thought.5

1. S. Lydakis, History of Modern Greek Painting [in Greek], vol. 3, Melissa publ., Athens 1976 p. 472.

2. See R. Kendall, Van Gogh to Picasso, The Berggruen Collection at the National Gallery, National Gallery publ., London 1991, pp. 74-77.

3. Compare Seaside landscape (C. Christou, C. Parthenis Vienna-Paris-Athens, Foundation for Hellenic Culture, Athens 1995, p. 64).

4. C. Christou, The Tree in the Greek Art of the 19th and 20th Century [in Greek] in The Tree, a Source of Inspiration and Creativity in Greek Art, exhibition catalogue, Averoff Museum, Metsovo and Nicosia Contemporary Art Center, Nicosia 1993, p. 19.

5. Z. Papantoniou, The Art of Parthenis [in Greek], Patris daily, 19.1.1920.