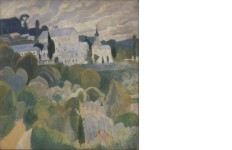

TITΛΟΣ ΕΡΓΟΥKARYES, SKETE OF THE THREE HIERARCHS AND THE HOLY TRINITY MONASTERIES

ΔΙΑΣΤΑΣΕΙΣ ΕΡΓΟΥΎψος : 54

Πλάτος : 50

ΥΛΙΚΟ ΚΑΤΑΣΚΕΥΗΣΕλαιογραφία (Λάδι σε χαρτόνι)

ΥΠΟΓΡΑΦΗ ΚΑΛΛΙΤΕΧΝΗΚάτω Δεξιά

ΧΡΟΝΟΛΟΓΗΣΗ01-01-1923

ΕΛΕΓΧΟΣ ΓΝΗΣΙΟΤΗΤΑΣΔεν έχει ελεγχθεί

Footnotes

Painted in 1923.

Bearing confirmation of authenticity (on the reverse) from Mina Papaloukas (artist's daughter).

Provenance:

Acquired directly from Mina Papaloukas, the artist's daughter, by the previous owner;

Private collection, Athens.

Literature:

Spyros Papaloucas, Sojourn service at Mt Athos, research and editing by M. Kambanis, Agioritiki Pinakothiki Mt Athos, 2003, no 26 (illustrated).

"Nature is god's miracle

and art is the miracle of man."

Spyros Papaloukas

Expansive in feeling and generous in scale - one of the largest formats the painter ever used - this exquisite canvas captures the spirit of magical Mt. Athos, a secluded place of prayer, serenity and contemplation, which has endured in an unbroken line for over a thousand years, continuing to enshrine the history and legend of Byzantium. A self-governing monastic state within the sovereignty of the Hellenic Republic, off-limits to women since AD 1060, Holy Mount Athos is home to Orthodox monks and hermits, who live in impressive monastic compounds surrounded by verdant hills and pine-clad forests.

Ιn early November 1923, Papaloukas, together with his close friend the writer and artist Stratis Doukas, went to Athos where he stayed for an entire year studying the rugged peninsula's luxuriant nature and setting out to tame its 'untameable'1 sea of green while capturing the mystery of the man-made environment that seems to be springing forth from the arcadian landscape. As Professor A. Prokopiou notes "in his Mt. Athos paintings, Papaloukas introduces the iconography of the rural abode that would be imitated later by most Greek landscape painters."2 The artist roamed the holy mountain, painting exquisite views of the ruling monasteries and the many and various Athonite colonies, including the dozen or so sketes -clusters of cottages several as big as their mother monasteries- and the kellia, small, isolated dwellings dotting the peninsula's forests and hilltops.3 Having amassed an impressive collection of material -including over one hundred oils, the two friends retreated to a kelli in Karyes, where they were visited by Fotis Kontoglou who was there for a brief stay. While living in this humble abode, Papaloukas organised his material and prepared for a major showing which opened in Thessaloniki's White Tower in 1924. This exhibition met with great success,4 virtually launching the city's cultural revival following its liberation in 1912.5

As noted by Athens National Gallery Director M. Lambraki-Plaka, the artist's decision to go to Mt. Athos had a dual significance. He sought consolation, a cleansing from the recent Asia Minor tragedy, but mainly wished to re-immerse himself into the primal sources of tradition. The painter himself questioned how an artist could possibly create the Greek future if not thoroughly familiar with the Greek past. In the holy mountain, Papaloukas didn't only delve into the spiritual experience of the Orthodox faith and monastic life but also had the chance to further formulate his own view on a balanced approach to tradition. He sought not to imitate or revive the Byzantine tradition of icon-painting but, rather, to capture the very essence of the Greek past as a continuous cultural entity from ancient times to Byzantium to the modern era. This view of his was at odds with the dogmatic premise of his good friend Fotis Kontoglou, who rejected any association with western art, engrossed in the utopian vision of reviving the Byzantine pictorial tradition. On the contrary, Papaloukas looked to tradition for answers on key issues raised by both modern art and his personal expressive quest, as well as by broader artistic and ideological pursuits of his time.6 The painter once said in a conversation that "a genuine artist shouldn't exclusively rely on a single source, that is his borrowings from tradition. To stand and walk you need both legs, one is not enough. And the teachings of tradition are one leg only."7

By the mid 1920s, the 30s generation of Greek artists had already set its own agenda, which included the quest of Greekness -not so much in terms of natural or national specificities (Greek light, space, people) but through timeless ideals and values, as well as collective symbols and archetypal images of the Greek cultural tradition. Throughout the interwar period Greekness remained a key artistic concern not only in the visual arts, but in literature (George Seferis, Odysseus Elytis) and music (Manolis Kalomiris, Nikos Skalkotas) as well, providing a fresh impetus and successfully combined with avant-garde trends.8 One of the first to tackle Greekness in relation to the pursuits of modern art, Papaloukas engaged in a thorough study of the underlying principles of Byzantine art,9 which culminated in his work on Mt. Athos.

This output, ranking among the greatest and most enduring achievements of Modern Greek art, is a key chapter not only in the development of the painter's style but also in the evolution of Greek art in the early decades of the 20th century. As perceptively noted by art critic A. Kouria, "The works of Papaloukas with subjects taken from Mt. Athos constitute a comprehensive pictorial statement and a substantial contribution to Greek landscape painting. Moreover, beyond their purely pictorial values, they are repositories of a certain ethos, an attitude of broader import. With these works Papaloukas provided a composed yet daring answer to some of the period's foremost issues, such as those related to tradition and the nation's self knowledge."10 The Holy Mountain's infinite variations of green, filtered light, and complex monastic architecture posed new problems for Papaloukas but the painter loved the challenge. As he once said, "within the landscape one finds the valuable qualities of colour, tonality and design."11

In lot 23, this most characteristic Athonite landscape, probably painted in 1924 judging from its large-scale format (in 1923 he was there for only the last two months and moving around with large canvases in wintertime would have been problematic)12 Papaloukas demonstrated a creative fusion of a rich age-old tradition with the doctrines of modern art. As if he were making a Byzantine mosaic, he emphasised the flatness of the surface, while liberating colour from its obligation to faithfully describe the world of appearances. This perception, which was also of pivotal importance to the art of some of the leading French impressionists, Cezanne and the early 20th c. avant-garde, is reminiscent of the famous saying by Maurice Denis that a painting is first and foremost a flat surface with colours which have been arranged in a certain order.13 As Papaloukas himself once said, "up there, in Mt. Athos I clearly saw that art in all its great manifestations through the ages has always been about form and colour."14

The complex architecture of the monastic compound is captured in soft and cool tonalities, without intense gradations, bathed in an ethereal, diffused light. One almost believes that the Athonite skete is loosing its structural integrity and material substance, sinking in a tempestuous sea of green and reuniting with nature from whence ideal, timeless forms originate. As noted by the director of the National Gallery in Athens M. Lambraki-Plaka, "Papaloukas' expertly trained eye reveals the 'eternal becoming' of the world."15

While the man-made environment seems dematerialised, suspended between earth and heaven, the verdant landscape, rigorously executed and accented with colour, takes on the leading role. The lush vegetation is rendered as overlapping patches of colour, distributed throughout the picture plane and applied with wide brushstrokes, forming an almost abstract pattern which creates ambivalence as to whether the space is actually receding or moving forward. Radiating patterns of intense brushwork and curvilinear forms translated into trees and foliage seem to wrench the composition away from the conventional recession into depth and pull it forward to the frontal plane in an innovative understanding of space that echoes some of Braque's most accomplished landscapes from the early 1900s.

Landscape at la Ciotat at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, which Braque painted in the summer of 1907, suggests a luminous Mediterranean countryside suffused with glaring light and blazing colour, but the composition is rigorous in structure. The landscape is defined by strong contours, and instead of appearing to recede as they mount towards the high horizon line, its elements mass and bulk as they climb the canvas, as if, rather than growing more distant, they were simply arranged on different levels.16 In this picture, as in Papaloukas', the artists' interest is structural as much as chromatic -they both employ colour not to decorative but to constructive use, controlling its abundant energy through the undulating curvilinear elements with which they hold their compositions together.

It is also interesting to compare Papaloukas' painting to The Climbing Path, L'Hermitage, Pontoise (1875, Brooklyn Museum, New York) by Camille Pissarro, whose style was equally derived from impressionist ideas of reality as a visual realm and traditional theories of landscape as a harmonious interplay among diverse forms. Both painters deliberately chose to explore the inter-relationship between the dominant motif of the picture (a rural cottage in the northwestern suburbs of Paris / a monastic skete in Mount Athos) and the foreground which provided the setting. Both have concentrated on reducing their compositions to basic structural elements and then arrange them frontally in successive rising planes, exploiting at the same time the interplay between straight and curved lines. Furthermore, in Papaloukas' picture, the dense foliage opens out to the extreme left to indicate a receding path caught in light, echoing Pissaro's own which daringly extends upwards at the extreme right edge of the canvas like a shaken out piece of silk.17 Although both pictorial devices seem to be suspended in the air, they are finally stabilised by the painters' convincing sense of form and overall compositional rhythm.

In one of the most perceptive texts ever written on Papaloukas, leading art critic E. Vakalo noted: "Papaloukas' Mt. Athos output is dominated by the study of the rhythm set by the dense chromatic volumes of the verdant flora in concert with the architectural elements of the monastic compounds. Many different approaches are evident. From the schematisation of form to the successive and overlapping wooded planes which unfold as volumes, the direction of the brushstrokes that follows the movement of the forms, and the lower to higher perspective that follows the composition's ascending organization; generally the handling of the composition as a rhythm that develops towards the limits of the canvas."18 Moreover, Mt. Athos' mountainous terrain embracing the sketes and monasteries, offered Papaloukas an ideal opportunity to almost exclude the horizon from many of his paintings. The acute luminosity of the Greek light, which clearly delineates even the remotest of mountains, justifies such an interpretation of space. By adhering to a solid compositional scheme and inner rhythm, Papaloukas, a true master of 20th c. Greek landscape painting, rediscovered the "natural continuum" that underlies and binds all things together.19

1. S. Doukas, 'Spyros Papaloukas' [in Greek], Zygos journal, no.31, May-June 1958, p. 7. See also Doukas, 'The Painter Spyros Papaloukas in Mt. Athos' [in Greek], Epitheorisi Technis journal, no.31, July 1957, pp. 44-47.

2. A. Prokopiou, History of Art 1750-1950, vol.2 [in Greek], Athens, 1968, p. 497.

3. See J.J. Norwich, 'Something of Byzantium' in Mount Athos, Hutchinson of London, 1966, pp. 45-46.

4. See M. Lambraki-Plaka, 'Papaloukas' Painting' in Spyros Papaloukas, Painting 1892-1957 [in Greek], Ionian Bank publ., Athens 1995, pp. 20-22. A significant number of paintings exhibited were sold in the first few days. See Doukas, 'Spyros Papaloukas', p. 10.

5. Doukas, 'The Painter Spyros Papaloukas' [in Greek], Diagonios journal, April-June 1966, p. 89. Exhibitions of such artists as Maleas and Gounaropoulos had been organised in Thessaloniki as early as 1914, the most important, however, being that of Papaloukas in 1924. See M. Papanikolaou, 'The Echo of Byzantine Art in the 1930s Generation, The Case of Spyros Papaloukas' [in Greek] in From Post-Byzantine to Modern Art, 18th-20th C., conference minutes (20-21 Nov. 1997), University Studio Press, Thessaloniki 1998, p. 297.

6. Lambraki-Plaka, 'Papaloukas' Painting, a Spiritual Adventure' [in Greek] in Spyros Papaloukas, exhibition catalogue, B&M Theocharakis Foundation for the Fine Arts and Music, Athens 2009, p. 14. See also Lambraki-Plaka, 'The Poetics of Spyros Papaloukas, Tradition and Artistic Creation' [in Greek], Zygos journal, no.10-11, September-December 1974, pp. 20-27.

7. As recorded by the icon painter C. Xinopoulos, June 1956, cited in Spyros Papaloukas, B&M Theocharakis Foundation, p. 102.

8. See H. Kambouridis - G. Levounis, Modern Greek Art - The 20th Century, Athens 1999, pp. 60-61.

9. See D. Papastamos, Painting 1930-1940 [in Greek], Astir Insurance publ., Athens 1981, p. 115; E. Vakalo, The Character of Postwar Art in Greece [in Greek], vol. 3, Athens 1983, p. 32; M. Papanikolaou, p. 298.

10. A. Kouria, 'Spyros Papaloukas' Athos' in Spyros Papaloukas, Apprenticing in Mt. Athos [in Greek], Athos 2003, p. 22.

11. Lambraki-Plaka, 'Papaloukas' Painting', p.37

12. M. Kambanis, 'Introductory Note' [in Greek] in Apprenticing in Mt. Athos, p. 11.

13. M. Denis, Theories, Paris 1920.

14. See G. Gavalaris, 'Spyros Papaloukas: Longing for Infinity' in Apprenticing, pp. 23-30.

15. See Lambraki-Plaka, 'Papaloukas' Painting', pp. 33-48.

16. See M. Dabrowski, 'French Landscape, The Modern Vision 1880-1920', exhibition catalogue, The Museum of Modern Art, new York 1999, p. 97.

17. See 'Pissaro', exhibition catalogue, Hayward Gallery, London; Grand Palais, Paris; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1981, p. 106.

18. E. Vakalo, 'Papaloukas' Painting' in Spyros Papaloukas, Painting, pp. 150-151.

19. Lambraki-Plaka, 'Papaloukas' Painting', pp. 37, 39.